Fault Injection Simulation

Introduction

If you’re developing embedded systems, you’ve probably heard about fault injection attacks. These are attacks where an adversary deliberately corrupts a microcontroller’s operation. Think voltage glitching during a boot sequence to bypass authentication, or electromagnetic pulses to flip bits in cryptographic operations. The results can be devastating: bypassed security checks, extracted encryption keys, or completely compromised devices.

Traditionally, testing your code against these attacks meant investing in extensive hardware: signal generators, oscilloscopes, EM probes, and specialized glitching equipment that can easily cost thousands of dollars. Even then, setting up repeatable tests is time-consuming and requires significant expertise.

Software-based fault injection tools change this entirely. Instead of physical glitching, they simulate attack effects by manipulating code execution, flipping memory bits, or skipping instructions within a controlled environment.

The advantages are game-changing: software simulation runs orders of magnitude faster than hardware testing, letting you iterate on countermeasures in seconds rather than hours. You can also systematically test hundreds of different fault scenarios automatically. Far more than is practical with physical equipment.

What Is Fault Injection?

A fault attack is an active attack that aims to inject errors into a target device. These errors can be accomplished through several tampering methods. Typical target circuits include central processing unit (CPU) registers, memory, or program counters. Depending on the precision of the applied technique, the effects can vary from flipping certain single bits to causing random values in several bytes.

Common fault attacks include the following:

-

Clock glitching: Induces faults by sudden and short changes in the clock signal. When the clock signal is too fast, flip-flops are triggered before the input signal is stable, resulting in a metastable state. This disturbs or prevents instruction execution, as there is not enough time to complete them before the next clock cycle. After the glitch, the processor operates normally.

-

Voltage glitching: This attack is similar to clock glitching. The fault is induced by abrupt changes in the supply voltage. This modifies the timing properties of the CMOS logic, causing faults like instruction skipping. Furthermore, memories require a stable power supply to operate correctly.

-

Temperature attack: An integrated circuit (IC) is only specified for a specific temperature range. Outside this range, proper function is not guaranteed. Conceivable effects include the random modification of RAM cells through heating.

-

Electromagnetic Pulse (EMFI): This attack uses electromagnetic pulses to influence memory cells or general function. An active coil creates a magnetic field that induces eddy currents on the surface near conductive materials. When used precisely, this technique allows for localized attacks.

-

Optical fault: A semi-invasive fault injection attack carried out using light pulses or high-intensity lasers. It is a local and precise attack that requires access to the bare silicon of the chip (usually through the backside nowadays).

Effects of Fault Attacks

The following effects of fault attacks are possible on a microcontroller. These effects are often referred to as fault models, which describe how a fault may manifest in the system. Understanding fault models is essential for simulating realistic attacks and developing effective countermeasures.

These are some basic fault models frequently observed in practice:

-

Data/code modification: Affects stored data in memory, particularly SRAM or FLASH memory. This can range from unpredictable values at various locations to flipping specific bits or bytes.

-

Register modification: Directly affects CPU registers. Especially in the program counter (PC), this modification allows an attacker to jump to any location in the code and control the program flow.

-

CPU execution corruption: Changes the instruction of an opcode. Depending on the precision of the attack, this corruption can skip an instruction or change it to a valid, random, or specific value.

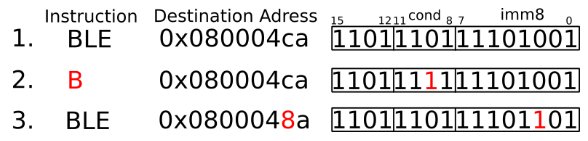

The picture illustrates an example of instruction corruption. This example uses a Thumb2 16-bit conditional branch. These branches are conditioned on the status register. Bits 15–12 of the opcode encode the instruction as a conditional branch, bits 11–8 encode the condition, and bits 7–0 encode the offset from the PC to the destination address.

Instruction (1) is a “branch if less or equal” instruction, which is common at the end of a loop, just after a comparison of the loop counter. The modification of a few bits can cause completely different program behavior. Instruction (2) changes from “branch if less or equal” to “branch always” by flipping a single bit in the condition field. Instruction (3) changes the address field to jump to a different location in the code. An adversary can use these effects to bypass access or write control verification. The attacker can also generate faulty encryptions or signatures, from which secret keys can be extracted.

Countermeasures

There are many different concepts for countermeasures. While many are implemented in hardware, our focus will be on software countermeasures, since we will be working with simulation-based fault injection. Software countermeasures can be applied against a wide variety of attacks and are often easier to prototype and evaluate in a simulated environment.

For example, consider the earlier scenario in which a conditional branch instruction was corrupted to always branch. A basic software countermeasure could be duplicating the condition check and branching logic in separate parts of the code, making it harder for a single fault to bypass the check. Alternatively, control-flow integrity techniques can detect unexpected instruction flows caused by such corruptions.

These examples highlight how simulation can help you test and refine such software-based defenses efficiently.

Why simulate Fault Injection?

Simulating fault injection offers significant advantages across development, testing, and security evaluation. One of the main motivations is cost and reproducibility. Hardware fault injection setups are expensive and not easily repeatable. Simulation enables automated, repeatable testing at a much lower cost.

Designing software countermeasures is also particularly challenging. Even if a countermeasure is implemented, it might still be bypassed, and the nature of fault effects is not always evident at the level of a high-level programming language. Developers must often analyze the behavior at the assembly level to truly understand vulnerabilities. Countermeasures tend to grow more complex as attack methods evolve, and compilers may even unintentionally undermine these protections.

Compared to hardware testing, simulation enables faster development cycles. There’s no need to launch a new test campaign for every code update, something especially valuable when working with non-reprogrammable memory like masked ROM. It also encourages rapid experimentation with new ideas. Moreover, simulation avoids the risk of physically damaging hardware, such as through overheating or overvolting a development board.

Simulations are also easier to run systematically. Instead of manually performing each test, you can automate hundreds of fault scenarios in a controlled and reproducible way. These tests can target specific fault models, allowing for thorough and targeted analysis. On the other hand, hardware-based setups often generate faults based on the characteristics of the physical equipment used. As a result, the exact fault behavior may not always be clear, consistent, or even fully understood.

Simulation is particularly well suited for early development, theoretical exploration of attack strategies, and refining software countermeasures before deploying to real hardware.

The Tool

Different tools exist for software-based fault injection. Most are based on the Unicorn Engine, which itself is a CPU emulator built on QEMU. Occasionally, commercial tools appear on the market, but they rarely gain traction or long-term support. One notable open-source tool is the one from Ledger: https://github.com/Ledger-Donjon/rainbow.

The tool we focus on here started simple but has gradually been extended. It is written in Rust, open source, and available on GitHub at https://github.com/tigger1005/fault_simulator. I’ve made small contributions to the project myself. We write our test code in C, using #define macros to indicate success or failure paths. The tool takes this code, compiles it using GCC, loads the resulting binary into a Unicorn Engine instance, and emulates its execution while injecting faults.

The tool includes several fault models:

- Glitch: Inject a program counter (PC) glitch that skips between 1 and 10 assembly instructions.

- Register Bit Flip: Flip bits in general-purpose registers (R0–R12) using XOR with a hex mask (single-bit only).

- Register Flood: Overwrite a register with either 0x00000000 or 0xFFFFFFFF.

- Command Fetch Bit Flip: Flip single bits in instructions during fetch.

After injecting faults, the tool checks whether the fault was successful or not. It also creates detailed instruction traces that show exactly where the fault was injected. To aid in visualization, a Ghidra plugin is available, allowing users to correlate trace data with disassembled code more intuitively.

Currently, the tool supports only ARM-M processors. This lets us test how firmware responds to faults and improve its resilience.

Demo

Once the fault simulator is installed according to the README, we can start our first simulation. We’ll begin by copying one of the provided examples:

cp content/src/examples/main_0.c content/src/main.c

This is a very basic C example demonstrating a branching decision. The code defines two possible execution paths, one for success and one for failure, using macros provided by the simulator:

int main()

{

int ret = -1;

decision_activation();

serial_puts("Some code 1...");

if (DECISION_DATA == success)

{

serial_puts("Verification positive path : OK");

start_success_handling();

ret = 0;

}

else

{

serial_puts("Verification negative path : OK");

__SET_SIM_FAILED();

ret = 1;

}

return ret;

}

void start_success_handling(void)

{

__SET_SIM_SUCCESS();

}

In this example, DECISION_DATA is evaluated. If the condition is met, a success message is printed and __SET_SIM_SUCCESS(); is called. This marks the simulation as successful. Otherwise, the program follows a failure path and calls __SET_SIM_FAILED();, indicating an expected failure. Under normal conditions, only the failure marker should be triggered. If a fault is injected that alters the control flow e.g., by corrupting the conditional branch, then the success path may be erroneously taken. This makes it an ideal case for testing whether such a fault could be exploited.

We start a single glitch attack with analysis using the following command:

cargo run -- --class single glitch --analysis

Output will be:

--- Fault injection simulator: 1342106-modified ---

Compile victim if necessary:

Compilation status: OK

Check for correct program behavior:

Verification positive path : OK

Verification negative path : OK

Program checked successfully

Run fault simulations:

Running simulation for faults: [Glitch (glitch_1)]

-> 35 attacks executed, 3 successful

Attack number 1

0x8000614: ldr r2, [r1], #0x1c -> Glitch (glitch_1)

"/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":47

Attack number 2

0x80004A2: bne #0x8000494 -> Glitch (glitch_1)

"/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":8

Attack number 3

0x800061C: cbnz r0, #0x8000630 -> Glitch (glitch_1)

"/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":49

Overall tests executed 35

List trace for attack number : (Return for exit):

The simulation was completed and we had 3 successful attacks. by choosing trace 1 we get the follwoing:

Assembler trace of attack number 2

0x8000000: bl #0x8000608 < NZCV:0000 >

__SET_SIM_FAILED(); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":43

0x8000608: push {r7, lr} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x00000000 LR=0x08000005 >

0x800060A: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF8 SP=0x2000FFF8 >

ret = 1; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":44

0x800060C: bl #0x8000008 < NZCV:0000 >

__attribute__((used, noinline)) void decision_activation(void) {} - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/common.c":16

0x8000008: push {r7} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF8 >

0x800000A: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF4 SP=0x2000FFF4 >

0x800000C: mov sp, r7 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF4 SP=0x2000FFF4 >

0x800000E: pop {r7} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF8 >

0x8000010: bx lr < NZCV:0000 LR=0x08000611 >

return ret; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":47

0x8000610: ldr r1, [pc, #0x2c] < NZCV:0000 R1=0x20000004 PC=0x08000612 >

0x8000612: adds r0, r1, #4 < NZCV:0000 R0=0x20000008 R1=0x20000004 >

-> Glitch (1 assembler instruction) (original instruction: ldr r2, [r1], #0x1c)

0x8000618: bl #0x800048c < NZCV:0000 >

memcmp(const void *str1, const void *str2, size_t count) { - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":4

0x800048C: push {r7} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF8 >

0x800048E: add r2, r0 < NZCV:0000 R2=0x20000008 R0=0x20000008 >

0x8000490: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFF4 SP=0x2000FFF4 >

while (count-- > 0) { - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":8

0x8000492: b #0x80004a0 < NZCV:0000 >

0x80004A0: cmp r0, r2 < NZCV:0110 R0=0x20000008 R2=0x20000008 >

0x80004A2: bne #0x8000494 < NZCV:0110 >

return 0; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":13

0x80004A4: movs r0, #0 < NZCV:0110 R0=0x00000000 >

} - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":14

0x80004A6: mov sp, r7 < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFF4 SP=0x2000FFF4 >

0x80004A8: pop {r7} < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFF8 >

0x80004AA: bx lr < NZCV:0110 LR=0x0800061D >

- "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":49

0x800061C: cbnz r0, #0x8000630 < NZCV:0110 R0=0x00000000 >

* Function Name: start_success_handling - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":51

0x800061E: ldr r0, [pc, #0x24] < NZCV:0110 R0=0x08000660 PC=0x08000620 >

0x8000620: bl #0x800059c < NZCV:0110 >

void serial_puts(char *s) { - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":40

0x800059C: bx lr < NZCV:0110 LR=0x08000625 >

* \brief This function launch CM33 OEM RAM App. - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":53

0x8000624: bl #0x8000474 < NZCV:0110 >

0x8000474: push {r7} < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFF8 >

0x8000476: ldr r3, [pc, #0x10] < NZCV:0110 R3=0x0AA01000 PC=0x08000478 >

0x8000478: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFF4 SP=0x2000FFF4 >

0x800047A: mov.w r2, #0x11111111 < NZCV:0110 R2=0x11111111 >

0x800047E: str r2, [r3] < >

------------------------

List trace for attack number : (Return for exit):

A glitch attack skipped the instruction ldr r2, [r1], #0x1c at address 0x8000614, which was part of a memory comparison operation. This caused the conditional check DECISION_DATA == success to incorrectly evaluate as true, making the program execute the success path instead of the expected failure path. We could also examine the other successful attacks, but let’s move on to another example.

In content/examples/main_3.c we make use of a fault injection hardening macro introduced by ARM Trusted Firmware-M:

#define fih_uint_eq(x, y) \

(fih_uint_validate(x) && \

fih_uint_validate(y) && \

((x).val == (y).val) && \

fih_delay() && \

((x).msk == (y).msk) && \

fih_delay() && \

((x).val == FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK((y).msk)) \

)

This macro tries to perform a fault-injection-resistant equality comparison between two unsigned integers by validating both operands, comparing their values and masks with deliberate delays, and verifying the value matches the expected masked pattern. In our simulation we won’t consider random delays.

Looks pretty secure, doesn’t it? Well, as it turns out, this macro has a smaller attack surface but can still be circumvented by a register bit flip in R6. So we need to improve it—but that will not be part of this post.

Assembler trace of attack number 2

0x8000000: bl #0x8000608 < NZCV:0000 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":24

0x8000608: push {r4, r5, r6, r7, lr} < NZCV:0000 R4=0x00000000 R5=0x00000000 R6=0x00000000 R7=0x00000000 LR=0x08000005 >

0x800060A: sub sp, #0x24 < NZCV:0000 SP=0x2000FFC8 >

0x800060C: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFC8 SP=0x2000FFC8 >

decision_activation(); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":26

0x800060E: bl #0x8000008 < NZCV:0000 >

__attribute__((used, noinline)) void decision_activation(void) {} - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/common.c":16

0x8000008: push {r7} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x800000A: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

0x800000C: mov sp, r7 < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

0x800000E: pop {r7} < NZCV:0000 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000010: bx lr < NZCV:0000 LR=0x08000613 >

serial_puts("Some code 1...\n"); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":28

0x8000612: ldr r0, [pc, #0xb4] < NZCV:0000 R0=0x08000700 PC=0x08000614 >

0x8000614: bl #0x800059c < NZCV:0000 >

void serial_puts(char *s) { - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":40

0x800059C: bx lr < NZCV:0000 LR=0x08000619 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000618: ldr r2, [pc, #0xb0] < NZCV:0000 R2=0x20000008 PC=0x0800061A >

0x800061A: add.w r5, r7, #0x18 < NZCV:0000 R5=0x2000FFE0 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

0x800061E: ldr r3, [pc, #0xb0] < NZCV:0000 R3=0xA5C35A3C PC=0x08000620 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000620: ldm.w r2, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0000 R2=0x20000008 R0=0xAAAA5555 R1=0x0F690F69 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

0x8000624: stm.w r5, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0000 R5=0x2000FFE0 R0=0xAAAA5555 R1=0x0F690F69 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000628: ldr r1, [r7, #0x1c] < NZCV:0000 R1=0x0F690F69 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

if (x.val != x_msk) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":125

0x800062A: ldr r2, [r7, #0x18] < NZCV:0000 R2=0xAAAA5555 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x800062C: eors r3, r1 < NZCV:1000 R3=0xAAAA5555 R1=0x0F690F69 >

if (x.val != x_msk) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":125

0x800062E: cmp r3, r2 < NZCV:0110 R3=0xAAAA5555 R2=0xAAAA5555 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000630: beq #0x8000636 < NZCV:0110 >

0x8000636: ldr r4, [pc, #0x9c] < NZCV:0110 R4=0x080006F8 PC=0x08000638 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

0x8000638: ldr r2, [pc, #0x94] < NZCV:0110 R2=0xA5C35A3C PC=0x0800063A >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x800063A: ldm.w r4, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0110 R4=0x080006F8 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x800063E: stm.w r5, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0110 R5=0x2000FFE0 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x8000642: strd r0, r1, [r7] < NZCV:0110 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

0x8000646: ldr r1, [r7, #0x1c] < NZCV:0110 R1=0xF096F096 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

if (x.val != x_msk) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":125

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000648: ldr r3, [r7, #0x18] < NZCV:0110 R3=0x5555AAAA R7=0x2000FFC8 >

uint32_t x_msk = FIH_UINT_VAL_MASK(x.msk); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":123

0x800064A: eors r2, r1 < NZCV:0010 R2=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

if (x.val != x_msk) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":125

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x800064C: cmp r2, r3 < NZCV:0110 R2=0x5555AAAA R3=0x5555AAAA >

if (x.val != x_msk) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/include/bootutil/fault_injection_hardening.h":125

0x800064E: beq #0x8000654 < NZCV:0110 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000654: add.w r3, r7, #8 < NZCV:0110 R3=0x2000FFD0 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000658: ldr r6, [pc, #0x7c] < NZCV:0110 R6=0x20000004 PC=0x0800065A >

0x800065A: ldm.w r4, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0110 R4=0x080006F8 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

-> Register BitFlip (Reg: R6, Value: 00000008) 0x20000004 -> 0x2000000c

0x800065E: ldr r2, [r6, #4] < NZCV:0110 R2=0x5555AAAA R6=0x2000000C >

0x8000660: stm.w r3, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0110 R3=0x2000FFD0 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x8000664: ldr r3, [r7, #8] < NZCV:0110 R3=0x5555AAAA R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000666: cmp r2, r3 < NZCV:0110 R2=0x5555AAAA R3=0x5555AAAA >

0x8000668: beq #0x8000680 < NZCV:0110 >

0x8000680: bl #0x800003c < NZCV:0110 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":104

0x800003C: push {r7} < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

}; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":108

0x800003E: movs r0, #1 < NZCV:0010 R0=0x00000001 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":104

0x8000040: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

}; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":108

0x8000042: mov sp, r7 < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

0x8000044: pop {r7} < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000046: bx lr < NZCV:0010 LR=0x08000685 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x8000684: cmp r0, #0 < NZCV:0010 R0=0x00000001 >

0x8000686: beq #0x800066a < NZCV:0010 >

0x8000688: add.w r3, r7, #0x10 < NZCV:0010 R3=0x2000FFD8 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x800068C: ldr r2, [r6, #8] < NZCV:0010 R2=0xF096F096 R6=0x2000000C >

0x800068E: ldm.w r4, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0010 R4=0x080006F8 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x8000692: stm.w r3, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0010 R3=0x2000FFD8 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x8000696: ldr r3, [r7, #0x14] < NZCV:0010 R3=0xF096F096 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000698: cmp r2, r3 < NZCV:0110 R2=0xF096F096 R3=0xF096F096 >

0x800069A: bne #0x800066a < NZCV:0110 >

0x800069C: bl #0x800003c < NZCV:0110 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":104

0x800003C: push {r7} < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

}; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":108

0x800003E: movs r0, #1 < NZCV:0010 R0=0x00000001 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":104

0x8000040: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

}; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/fault_injection_hardening.c":108

0x8000042: mov sp, r7 < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

0x8000044: pop {r7} < NZCV:0010 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x8000046: bx lr < NZCV:0010 LR=0x080006A1 >

if (fih_uint_eq(DECISION_DATA, FIH_SUCCESS)) - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":30

0x80006A0: cmp r0, #0 < NZCV:0010 R0=0x00000001 >

0x80006A2: beq #0x800066a < NZCV:0010 >

0x80006A4: ldr r2, [r6, #4] < NZCV:0010 R2=0x5555AAAA R6=0x2000000C >

0x80006A6: ldr r3, [pc, #0x28] < NZCV:0010 R3=0xA5C35A3C PC=0x080006A8 >

0x80006A8: ldm.w r4, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0010 R4=0x080006F8 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x80006AC: stm.w r5, {r0, r1} < NZCV:0010 R5=0x2000FFE0 R0=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x80006B0: ldr r1, [r7, #0x1c] < NZCV:0010 R1=0xF096F096 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

0x80006B2: eors r3, r1 < NZCV:0010 R3=0x5555AAAA R1=0xF096F096 >

0x80006B4: cmp r2, r3 < NZCV:0110 R2=0x5555AAAA R3=0x5555AAAA >

0x80006B6: bne #0x800066a < NZCV:0110 >

serial_puts("Verification positive path : OK\n"); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":32

0x80006B8: ldr r0, [pc, #0x28] < NZCV:0110 R0=0x08000710 PC=0x080006BA >

0x80006BA: bl #0x800059c < NZCV:0110 >

void serial_puts(char *s) { - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/utils.c":40

0x800059C: bx lr < NZCV:0110 LR=0x080006BF >

ret = 0; - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":34

0x80006BE: movs r0, #0 < NZCV:0110 R0=0x00000000 >

start_success_handling(); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":33

0x80006C0: bl #0x8000474 < NZCV:0110 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":55

0x8000474: push {r7} < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFC8 >

__SET_SIM_SUCCESS(); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":56

0x8000476: ldr r3, [pc, #0x10] < NZCV:0110 R3=0x0AA01000 PC=0x08000478 >

{ - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":55

0x8000478: add r7, sp, #0 < NZCV:0110 R7=0x2000FFC4 SP=0x2000FFC4 >

__SET_SIM_SUCCESS(); - "/home/fisim/fault_simulator/content/src/main.c":56

0x800047A: mov.w r2, #0x11111111 < NZCV:0110 R2=0x11111111 >

0x800047E: str r2, [r3] < >

------------------------

List trace for attack number : (Return for exit):

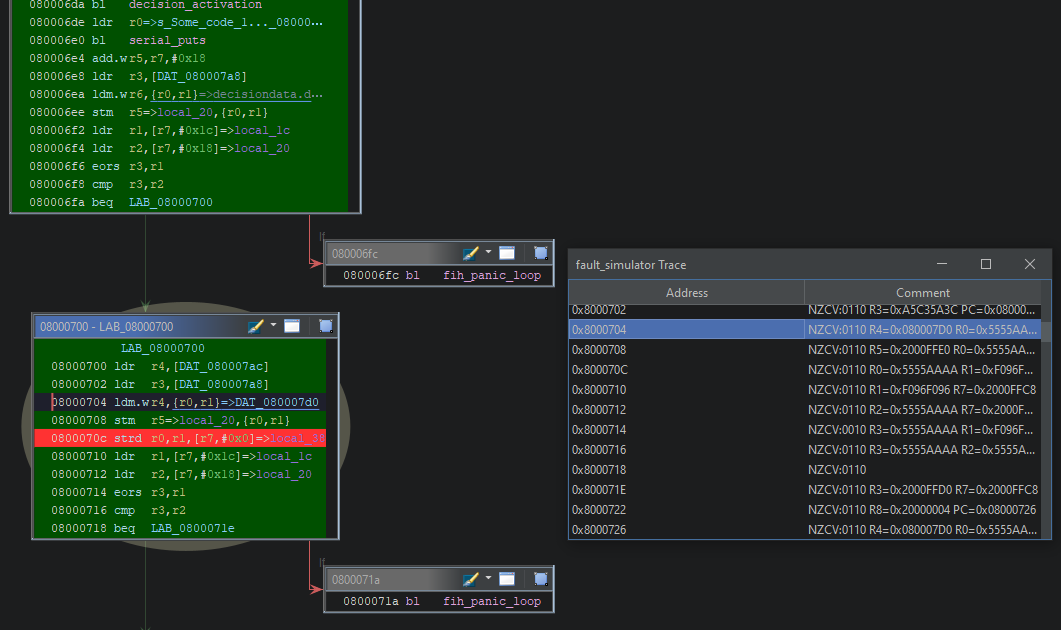

As the complexity increases, it becomes harder to understand what’s happening just by looking at the trace in the shell. To address this, I created a Ghidra plugin where you can paste the trace, and it will highlight the program flow in the listing and let you step through the trace.

Ghidra plugin to visualize the fault trace

Ghidra plugin to visualize the fault trace

Limitations

There are several limitations to keep in mind when using this type of simulation. First, it’s a model, meaning it doesn’t capture real analog behavior such as timing glitches or race conditions. As a result, it may miss certain real-world interactions, like peripheral behaviour or faults triggered by precise timing conditions. The simulation covers only CPU and memory corruption and does not extend to other components. It also doesn’t replace physical testing when it comes to side-channel or timing attacks. Although similar simulation-based approaches exist for evaluating side-channel vulnerabilities, they come with their own limitations and trade-offs.

Future improvements/ideas

It would be great to test components of a complete firmware directly, without having to compile them ourselves. To enable this, we would likely need to simulate or stub hardware behavior so that code dependent on hardware interaction can be tested as well.